In Latter-day Saint theology, is God all-powerful? The answer depends on how one defines omnipotence. According to scripture and Church doctrine, the answer is unequivocally yes. However there are important caveats. In this essay, I explore what is sometimes called Mormon finitism, the idea that God’s power is limited, and discuss its significance.

Table of Contents

What Does Omnipotence Mean Under Classical Theism?

What Is Mormon Finitism?

God’s Omnipotence Is Clearly Taught in Scripture. Does It Not Contradict Mormon Finitism?

God’s Limits Explained

Limit 1: God Cannot Create Matter Ex Nihilo

Limit 2: God Cannot Create or Destroy Intelligences

Limit 3: God Cannot Advance His children to Become Like Himself Without Having Them Experience Life in a Fallen World.

Limit 4: God Cannot Violate Eternal Laws Related to His Perfect Nature

Limit 5: God Could Not Have Brought About the Effects of the Atonement Without Jesus Christ’s Suffering and Death

Mormon Finitism and the Problem of Evil

A Caution Against Over-Applying the Limits on God’s Power

Is a God of Limited Power Worthy of Worship?

Why Have I Not Heard of This?

Conclusion

What Does Omnipotence Mean Under Classical Theism?

Classical theism refers to the traditional view of God held in much of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Under this view, God’s omnipotence is often taken at face value to mean simply that God can do anything without any limits. But philosophers and theologians have long recognized it is not so simple. We have all heard the question, “While remaining omnipotent, can God create a rock so big He cannot lift?” In response to questions like these, philosophers of religion have advanced numerous interpretations of what it means for God to be all-powerful. Broadly, there are two main positions:

God can do anything, even the logically impossible.

This position is not popular among philosophers and theologians, as it leads to logical and philosophical problems.

God can do anything within the bounds of logic.

This is the most widely accepted view. It means God cannot construct a square circle, create a married bachelor, or make 2+2=5. But God can do anything that is logically valid.

C. S. Lewis explained it this way:

His Omnipotence means power to do all that is intrinsically possible, not to do the intrinsically impossible. You may attribute miracles to Him, but not nonsense. This is no limit to His power. If you choose to say “God can give a creature free-will and at the same time withhold free-will from it,” you have not succeeded in saying anything about God: meaningless combinations of words do not suddenly acquire meaning simply because we prefix to them the two other words “God can”. It remains true that all things are possible with God: the intrinsic impossibilities are not things but nonentities. […] Nonsense remains nonsense even when we talk it about God.1

On the “rock so big” puzzle, God’s omnipotence means He can create a rock of any size and can lift a rock of any size. Thus, any rock He creates, He can lift. Under this view of classical theism, God cannot create a rock so big He cannot lift. To assert otherwise would be to claim the existence of a rock whose size is not included by the words “any size,” something that makes no logical sense.

What Is Mormon Finitism?

Within Latter-day Saint thought, God’s limits extend beyond the logical boundaries recognized in classical theism. In the philosophy of religion, this is referred to as theistic finitism. The Latter-day Saint version is commonly called Mormon finitism.

While the underlying doctrines that give rise to Mormon finitism are widely held beliefs, consolidating them into a view of theistic finitism is not commonly known or taught. I discuss this further in the “Why Have I Not Heard of This?” section below. So in this essay, I am developing this concept using my own reasoning, guided by the scriptures and Church teachings as I understand them. On that basis, I identify five substantive limits to God’s power:

God cannot create matter ex nihilo (out of nothing) or destroy it into nothing; He can only organize preexisting matter (creatio ex materia).

God cannot create or destroy intelligences.

God cannot advance His children to become like Himself without having them experience life in a fallen world.

God Cannot Violate Eternal Laws Related to His Perfect Nature.

God could not have brought about the effects of the Atonement without Jesus Christ’s suffering and death.

This goes beyond purely logical constraints, which is why the Latter-day Saint position is considered a form of theistic finitism.

God’s Omnipotence Is Clearly Taught in Scripture. Does It Not Contradict Mormon Finitism?

It entirely depends on how the terms omnipotent, all power, and related expressions are interpreted in the verses. As I will explain, I think there is a reasonable interpretation in which these teachings are not in contradiction with Mormon finitism.

God’s omnipotence is explicitly and frequently taught in scripture, and it is never given any caveats. To see this, here are three examples from the Book of Mormon:

Mosiah 4:9: “Believe in God; believe that he is, and that he created all things, both in heaven and in earth; believe that he has all wisdom, and all power, both in heaven and in earth…”

1 Nephi 7:12: “…the Lord is able to do all things according to his will.”

Ether 3:4: “And I know, O Lord, that thou hast all power, and can do whatsoever thou wilt for the benefit of man…”

These verses seem to contradict Mormon finitism. Can God do all things, or can He not? Does He have all power, or does He not? But it is important to note that the same question applies to classical theism as well. There is no biblical verse that says God cannot do the logically impossible. To borrow the classical theist reasoning, I will reassert the first part of C. S. Lewis’s quote cited above:

His Omnipotence means power to do all that is intrinsically possible, not to do the intrinsically impossible. You may attribute miracles to him, but not nonsense.

Lewis intended “impossible” and “nonsense” to apply solely to logical contradictions, not to theistic finitism. However, I believe his words can still be applied to interpret scriptural passages on God’s omnipotence in a finitist framework. God can do all that is possible, but there are some things that are fundamentally impossible, even if logically conceivable.

Yes, God can do all things, but creation ex nihilo, for example, is not actually a “thing” in the sense meant in that phrase. Creation ex nihilo exists as a concept, but does not exist as an actual thing in reality. As Lewis stated: “the intrinsic impossibilities are not things but nonentities.”

Of course, there is a big difference between logical and metaphysical impossibility. In the traditions of philosophy, the term “omnipotence” has generally allowed only limits on what is logically impossible. Thus, the God of Mormonism is not omnipotent in that traditional philosophical sense. Rather, in the traditions of Latter-day Saint thought, “omnipotence” allows for both logical and metaphysical limits. It means possessing all the power it is metaphysically possible to have.

God’s Limits Explained

Limit 1: God Cannot Create Matter Ex Nihilo

Doctrine and Covenants 93:33 states, “the elements are eternal.” Likewise, the Book of Abraham describes the Creation as a process of organizing preexisting material.2

Joseph Smith taught this principle, explaining:

Element had an existence from the time [God] had. The pure principles of element are principles that can never be destroyed; they may be organized and reorganized but not destroyed.3

He also stated:

God did not make the earth out of nothing; for it is contrary to a rational mind and reason that a something could be brought from a nothing; also it is contrary to the principle and means by which God does work.4

Many subsequent Church Presidents have affirmed this view, and it is a standard doctrine of the Church.

Are There Not Examples in Scripture of Creation Ex Nihilo, Such as When Jesus Fed the Five Thousand?

Many possible ex materia explanations exist for Jesus feeding the five thousand or for other biblical miracles. Perhaps the protons, neutrons, and electrons in air molecules were reorganized into the fish and loaves. Or perhaps new particles were formed upon exciting the underlying quantum fields. If a fourth spatial dimension exists, atoms could have entered from there, appearing to materialize out of nowhere to our perspective.

Regardless of the specific mechanism, no miracle in scripture contradicts the impossibility of creation ex nihilo.

What About E=mc²? Does This Not Disprove that Elements Are Eternal?

E=mc² demonstrates the interchangeability of matter and energy, meaning matter can be converted to energy and energy to matter. This might seem to disprove the doctrine of eternal elements. However, neither scripture nor any prophet has specified in this context what is meant by “matter,” “material,” or “elements,” and we should not expect them to. It is possible that energy is included among the “elements,” or that these references point to the quantum fields that, as understood in modern physics, pervade spacetime and underlie all physical reality. Perhaps they even refer to something more fundamental that remains unknown to current science.

Does the Big Bang Disprove an Eternal Reality?

The Big Bang Theory describes how the observable universe expanded from an extremely hot and dense state about 13.8 billion years ago. Importantly, it does not address the origin of that initial state or whether anything exists beyond the observable universe. As some Christians and classical theists misunderstand, the Big Bang does not imply a creation of everything ex nihilo. It merely describes the evolution of the cosmos from a given starting condition.

As the philosopher Wes Morriston put succinctly:

the Big Bang theory provides no support for the doctrine of creation ex nihilo5

This is also explained in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

There are good reasons to think that the big bang is not necessarily an absolute beginning.6

And a survey of physicists found that 68 percent state the Big Bang “says nothing about whether there was an absolute beginning of time or not”, with only 17 percent accepting it as such and the rest choosing other or no opinion.7

The Big Bang Theory need not contradict Mormon cosmology. While we can only speculate, one possibility is that God exists outside our observable universe, perhaps within a broader multiverse, and that during Creation He organized a hot, dense state from preexisting elements before causing their expansion in the Big Bang.

Is An Eternal Past Philosophically Impossible?

Many classical theists maintain that an infinite regress of causes is impossible. A chain of causation extending into the past must terminate in something uncaused, what they call the unmoved mover, or God. By necessity, only God alone exists without a cause, and everything else exists from a causal chain extending back to an initial act of creation ex nihilo by Him.8

Arguments both for and against the necessity of an absolute beginning can be made, but a full treatment of these arguments would be too long for this essay. I will simply note that in philosophy and science the matter is not settled.9

For a thorough analysis defending this from a Latter-day Saint perspective, see Blake Ostler’s paper Do Kalam Infinity Arguments Apply To The Infinite Past?

The Importance of the Doctrine of Eternal Elements

I used to consider the doctrine of eternal elements and God creating the universe ex materia as a relatively inconsequential point, more of a fun fact about God and Creation than anything with important philosophical implications. However, I have since concluded the opposite.

Later in this essay, I discuss how theistic finitism helps resolve major philosophical issues confronting classical theism. If that is truly the case, then why do not more theologians and philosophers simply propose a limited God? Some do,10 but the position becomes difficult to maintain while also believing in a world where everything was created by God ex nihilo. How can God be limited by what He created? Philosophers have recognized this issue. For example, Christian philosophers William Lane Craig and Paul Copan wrote

If matter were not itself created ex nihilo by God, then there would be something over which he lacked power, which contradicts his omnipotence.11

Since Latter-day Saint doctrine teaches that God exists within a reality He did not create, there also exists eternal laws that can constrain what is possible. God did not create these laws as they are co-eternal with Him. This means that although He can often alter reality by divine fiat, there are times when He must work through plans and processes because of the limits imposed by those eternal laws.

By contrast, it is difficult to imagine God creating a world with laws only to then be subject to the very laws He created. Without the doctrine of God being co-eternal with reality and the elements within it, Mormon finitism itself would be philosophically untenable.

A Note on “Eternal Law”

Throughout this essay, I use the term “eternal law.” I do not imagine these “laws” as distinct entities that exist independently, as we might think of legal laws. They are probably more like physical laws in the natural world, such as the laws of thermodynamics. These physical laws are descriptions of how the natural world functions, not separate things that exist within it. Similarly, eternal laws are probably not separate coexisting entities alongside God, but descriptions of how reality functions, a reality within which God exists and is therefore subject to its inherent possibilities and impossibilities.

Limit 2: God Cannot Create or Destroy Intelligences

According to Latter-day Saint doctrine, all human beings existed as intelligences before they became spirit children of God. This means that God did not create our fundamental essence or soul. Instead, He took these eternal intelligences and formed them into His spirit children, who later receive physical bodies at birth.

Scripture and statements from Church leaders have used the terms spirit and intelligence interchangeably. Nevertheless, the core doctrine is that at some fundamental level, who we are has always existed, including prior to becoming spirit children of God.

Doctrine and Covenants 93:29 states:

Man was also in the beginning with God. Intelligence, or the light of truth, was not created or made, neither indeed can be.

Joseph Smith similarly taught:

The spirit of man is not a created being, it existed from eternity, and will exist to eternity.12

But What Actually Is an Intelligence?

The exact nature of intelligences is not well defined in scripture or official Church teachings.13 Most people have some intuition of a “soul,” which likely approximates the idea, but even that term is difficult to pin down.

Though the following are well-established doctrines.

God formed us into His spirit children from preexisting intelligences.14

These intelligences are eternal and uncreated.15

Thus, we as humans are fundamentally eternal beings.

While it is well established that God formed us as His spirit children from already existing eternal intelligences, it is not settled whether God formed a single spirit child from a single, discrete intelligence, or whether we were formed from something more like intelligent matter.16 (Though I find the former perspective more convincing).

Regardless of which position one takes, the very naming of this stuff as “intelligence” strongly implies to me it is something inherently noetic or mindlike, not inert material. Whether this rises to the level of personal identity, consciousness, or agency is more speculative.17

The Importance of the Doctrine That We Existed Eternally as Intelligences

Just as the doctrine of eternal elements grounds Mormon finitism in general, the teaching that human beings existed eternally as intelligences prior to becoming spirit children of God provides philosophical support for the limits on God’s power in relation to the eternal progress of His children.

When God formed us into His spirit children, why did He not create us in a state of exaltation from the beginning? If He can reorganize the eternal elements to form worlds and heavens, why can He not simply form exalted beings?

If intelligences themselves were created by God out of more basic elements, it would imply that He could rearrange those elements and alter the intelligences at will. But intelligences are not the result of organizing raw materials. They are uncreated and therefore as fundamental as the eternal elements themselves. This fact does not logically prove that God cannot overwrite their intrinsic natures. However, it does provide the philosophical grounding for why such a limitation can plausibly exist.

We came to God as intelligences with existing natures. As I will explain further in the next section, God is limited in His ability to overwrite these natures instantly by divine fiat. So as a solution, He instituted a plan of salvation which includes life on a fallen world where our natures are progressed through experiences of suffering, joy, and the exercise of agency.

Limit 3: God Cannot Advance His children to Become Like Himself Without Having Them Experience Life in a Fallen World

If it were possible for God to grant exaltation without requiring us to endure the hardships of a fallen world, I believe He would. Why would an all-loving God subject His children to suffering and the risk of not obtaining a fulness of joy if a better option existed?

The Book of Mormon teaches the necessity of experiencing this mortal life. Alma 12:26 states:

If it were possible that our first parents could have gone forth and partaken of the tree of life they would have been forever miserable, having no preparatory state; and thus the plan of redemption would have been frustrated.

Partaking of the tree of life represents eternal life or exaltation, while the “preparatory state” refers to mortality in a fallen world. The conditional phrase “if it were possible” already questions whether exaltation without mortality is possible at all. Alma then clarifies that even if it were, it would result in misery. It is impossible for God to grant us exaltation with a fulness of joy without a preparatory state.

What Is This Preparatory State?

This preparatory state includes life on earth in a fallen condition where suffering, joy, doubt, and moral decision making are possible. Yet while all must come to earth, not all will have the same experiences.

In our pre-earth life, we already differed as spirits. Abraham 3:18–19 describes how spirits differ in “intelligence,” with God being the most intelligent of all. Abraham 3:22–23 speaks of God’s children in the pre-earth life who were the “noble and great ones.” These passages show that before coming to earth, we already had differing natures, and therefore our preparatory states will also differ.

This perspective may help explain why some are born into families where they learn the gospel, while others do not hear it until the spirit world; why some are naturally more skeptical, while others find faith easy; why some experience more hardship and pain in life than others; and why some die in infancy and bypass earthly moral testing altogether.

I believe God’s loving nature means He will not allow His children to have negative experiences, such as suffering or religious confusion, unless they are necessary, either directly or indirectly, for their own eternal progression or for the progression of others. Without theistic finitism, such a belief would be nearly impossible to sustain.

Limit 4: God Cannot Violate Eternal Laws Related to His Perfect Nature

Latter-day Saint doctrine teaches the Fall was a necessary part of God’s plan.

The Fall is an integral part of Heavenly Father’s plan of salvation. It has a twofold direction—downward yet forward. In addition to introducing physical and spiritual death, it gave us the opportunity to be born on the earth and to learn and progress.

– Gospel Topics: Fall of Adam and Eve

If life on earth in its fallen state is essential for our progression, one might ask: Why didn’t God simply create a fallen world from the outset? Why the extra step of the Garden of Eden?

Why Was the Garden of Eden Necessary?

(The following reasoning applies whether one views the accounts of Creation and the Garden of Eden as literal history or allegory. I’ll reason within the framework of the scriptural narrative, and you may interpret my arguments according to the same lens through which you understand that narrative.)

While no scripture or prophetic statement explicitly answers if and why the Garden of Eden was necessary, I think it can be reasonably inferred that directly creating a fallen world would have violated an eternal law tied to God’s perfect nature. Alma 42 teaches that if God were to act contrary to justice, He would “cease to be God” (Alma 42:13, 22, 25). This principle could be expanded to mean that God cannot act in violation of His own perfection more broadly.

Some may object that God Himself planted the Garden of Eden, including the tree of forbidden fruit, and permitted Satan to tempt Adam and Eve with the foreknowledge that they would transgress. How, then, is this different from God directly creating a fallen world? If an eternal law prevents God from directly causing something, would not indirectly causing it with the same intention still violate the “spirit” of that law?

From a moral perspective, I agree there is little relevant difference between directly and indirectly causing an outcome when the intention is the same. But I am not proposing a moral reason for why the Garden of Eden was necessary. God is not choosing this route simply because He prefers not to get His hands dirty while letting others be the scapegoat.

Rather, I am asserting that this is just how this eternal law works. As an analogy, no one argues that building an airplane is impossible or illegitimate because it violates the “spirit” of the law of gravity. In the same way, God works within the constraints of eternal law by setting up the conditions for the Fall to occur through Adam and Eve’s transgression, rather than directly creating a fallen world Himself.

As explained in the previous section, our progression toward divinity requires passing through a world filled with sin, suffering, and death. Yet eternal law and God’s nature prevent Him from simply creating such a world. This paradox is why the plan of salvation is the way it is. The three pillars of the plan of salvation: the Creation, the Fall, and the Atonement, exist precisely as God’s solution to the paradox.

What Counts as God Violating His Perfection

Not everything we might classify as “bad” falls under what God is unable to directly cause. The scriptures record many instances of God sending judgments, commanding destruction, or otherwise bringing about suffering and death.

My interpretation is that the Fall created the conditions that made such acts possible. God could not have sent a plague to inflict suffering and death upon Adam and Eve while they remained in the paradise of Eden. But once their transgression opened the door to a fallen world, then it became possible for God to send suffering, even upon the innocent, in order to create the experiences necessary for growth and development in this mortal life.

What does seem to fall under God’s limitations in relation to His perfection include His inability to lie and the necessity of the Atonement to satisfy the demands of justice.

God’s Perfection, His Inability to Lie, and Divine Hiddenness

Just as suffering is an important part of life in a fallen world, so too are doubt, confusion, and the necessity of faith. The intellectual struggle that often accompanies discipleship is an essential part of many people’s mortal experience. Philosophers of religion refer to the existence of this confusion as divine hiddenness, and many use it as an argument against God’s existence: if God is perfectly loving, why would He allow His existence and religious truth to remain less than obvious to all? For Latter-day Saints, the doctrines of the plan of salvation and the purpose of this earth life, grounded in theistic finitism, provide a powerful solution and show why divine hiddenness is essential.

An example of God choosing to bring about divine hiddenness appears in 2 Thessalonians 2:11–12:

11 And for this cause [of wickedness] God shall send them strong delusion, that they should believe a lie:

12 That they all might be damned who believed not the truth, but had pleasure in unrighteousness.

When Paul says that God will “send them strong delusion,” I do not interpret this to mean that God or His angels teach falsehoods, as this would contradict God’s restriction on lying. Rather, as with the Garden of Eden and the Fall, God can allow human error and the natural unfolding of events to create an environment where falsehoods, doubt, and confusion exist.

Of course, divine hiddenness is not universal or constant. At times God intervenes to correct falsehoods, perform miracles to affirm faith, answer prayers of doubt, or remove confusion. As with suffering, He determines when and to what degree it occurs.

This same principle may also explain why God works through prophets and scripture rather than, for example, assigning every person an angel to explain the gospel flawlessly. Prophets are prone to human error, and scripture can be miscopied, mistranslated, and misunderstood. God can intervene to correct such mistakes, but He can also allow them to persist according to His purposes. All of this is by design, allowing for the intellectual and spiritual struggle that many people require for their eternal progression.

The Latter-day Saint solution to divine hiddenness warrants its own dedicated essay for fuller clarification and exploration. But in summary, I believe the problem is intractable without theistic finitism.

Limit 5: God Could Not Have Brought About the Effects of the Atonement Without Jesus Christ’s Suffering and Death

When Jesus prayed in the Garden of Gethsemane, He pleaded with His Father to remove the suffering He was then enduring as He bore the sins of humanity, saying,

Father, if thou be willing, remove this cup from me: nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done.

– Luke 22:42

Why did God not remove this bitter cup? One answer is that doing so would have jeopardized the Atonement. But if God is omnipotent, could He not have brought about the effects of the Atonement without Christ’s suffering? In the history of Christian thought, two responses have been given. Necessitarians maintain that God could not forgive sin and grant salvation without Christ’s death, providing reasons of logical necessity to not contradict classical omnipotence. Non-necessitarians, by contrast, argue that God’s omnipotence means the Atonement was not necessary, but that He had other good reasons for it.

For Latter-day Saints, I would argue for a necessitarian view. As explained previously, God is unable to act in violation of His perfect nature. Because of the Fall and our sins, humanity is in the grasp of justice, which permanently separates us from God. He cannot simply command away the consequences of sin. The only solution is the Atonement of Jesus Christ, in which a sinless being, through His suffering, bridged the gulf that we cannot cross by the power of God alone.

Is It “Justice” to Torture an Innocent Third Party to Forgive the Sins of the Guilty?

What does the suffering of an innocent third party have to do with genuine justice? Thomas Paine raised this objection in The Age of Reason:

If I owe a person money, and cannot pay him, and he threatens to put me in prison, another person can take the debt upon himself, and pay it for me; but if I have committed a crime, every circumstance of the case is changed; moral Justice cannot take the innocent for the guilty, even if the innocent would offer itself. To suppose Justice to do this, is to destroy the principle of its existence, which is the thing itself; it is then no longer Justice, it is indiscriminate revenge.18

Imagine a guilty man standing before a king. The law demands his execution, and the king, being bound by justice, feels compelled to carry it out. The king’s innocent son sees the man’s remorse and volunteers to endure torture so that the man may go free. The king accepts this as a solution to satisfy the demands of justice. The son is then tortured, and the man is forgiven and released.

If this happened, we would recognize the king as having gone mad. If the man is repentant and the king can forgive him, then just forgive him. What does torturing an innocent third party have to do with it?

I agree this is not justice but actually a massive injustice. Under classical theism, this would be a strong critique. But for Latter-day Saints, theistic finitism allows for a solution. As I understand it, the term “justice” as used in the context of the Atonement does not refer to the moral principle of justice. Rather, it is the name given to an eternal law which God cannot violate. This law is not a law of logic or moral law, but a substantive restriction on God and therefore its existence is only compatible with finitism. When we sin, we mark our spirits as unworthy to live with God, a perfect and glorified being. Through mechanisms not known to us, the Atonement of Jesus Christ was the only solution.

So Why Is This Eternal Law Called “Justice”?

If this eternal law is not the same as the moral principle of justice, then why is it called “justice”? Because the term functions as a metaphor, borrowed from the notion of settling a debt.

Each of us lives on a kind of spiritual credit. One day the account will be closed, a settlement demanded.

…

By eternal law, mercy cannot be extended save there be one who is both willing and able to assume our debt and pay the price and arrange the terms for our redemption.

…

Through [Jesus Christ] mercy can be fully extended to each of us without offending the eternal law of justice.

– Elder Boyd K. Packer, “The Mediator,” April 1977 General Conference

Our sins are not literally financial debts, and Christ’s suffering is not literally a monetary payment to a creditor. The debt imagery is a metaphor to help us understand how the Atonement satisfies eternal law. The term “justice” is used because the moral principle of justice can be satisfied by an innocent third party when demanding payment for debt.

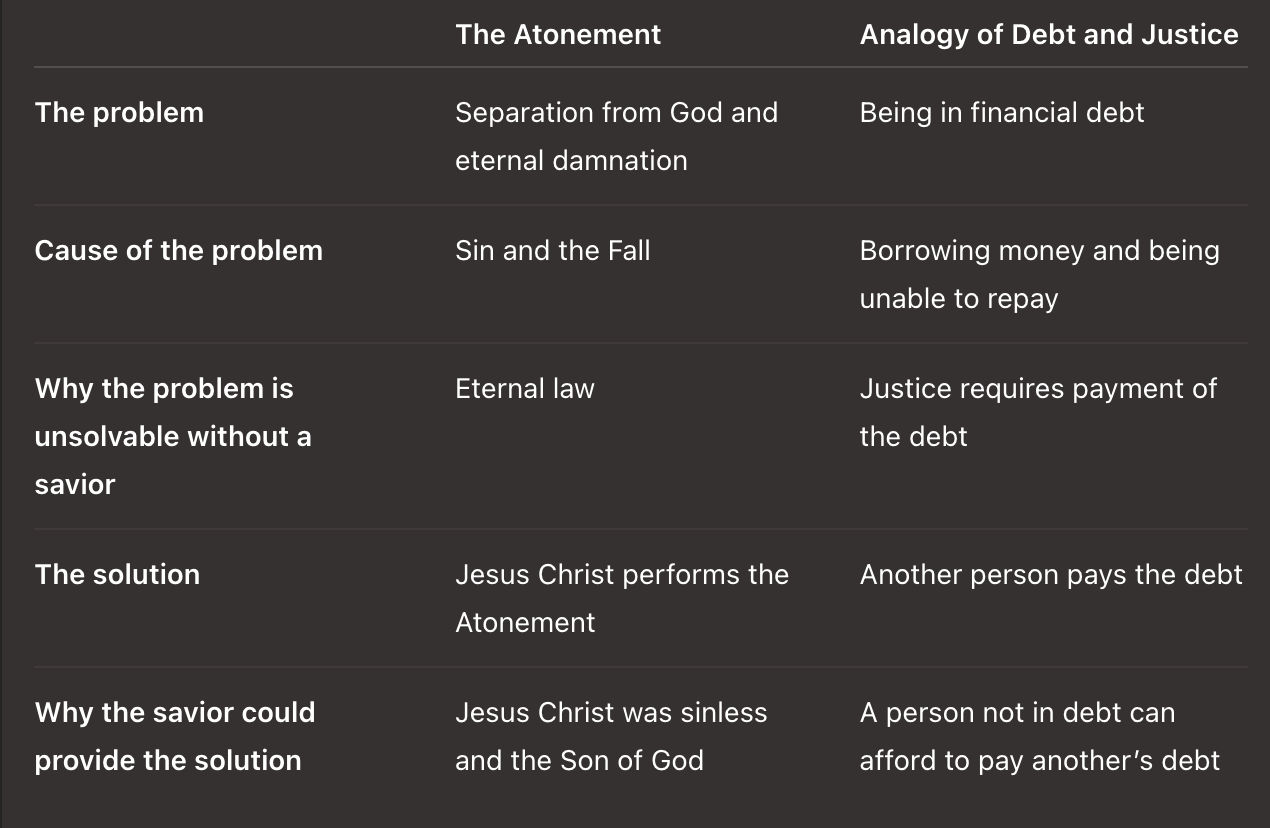

To help clarify, this table maps the same concept across the Atonement and this analogy of debt and justice:

Mormon Finitism and the Problem of Evil

Why does an all-loving and all-powerful God allow so much suffering? In the philosophy of religion, this is called the problem of evil, often considered by believers and non-believers alike as one of the most formidable challenges to classical theism. The Catholic priest and theologian Hans Küng described it as the “rock of atheism.”19

It might be better described as the problem of badness, since “evil” implies conscious intent from an agent, while the problem is meant to encompass anything we would consider “bad.” This includes everything from the destruction of war, to a child with brain cancer, to a deer starving in agony in the wild. Why would an all-loving God not intervene?

Theodicies – Responses to the Problem of Evil

Solutions to this problem are known as theodicies. For example, I have already described how God may permit suffering to facilitate spiritual growth. This is known as the soul-building theodicy.

Many classical theists also use the soul-building theodicy. But under their view, God could grant the same growth without the suffering, or even better, He could have created the person with that spiritual maturity from the beginning. One could insist that growth through struggle is somehow better, but whatever those additional benefits may be, a classically omnipotent God could have granted them as well.

In order for a theodicy to work under classical theism, the greater good that justifies the bad must be logically impossible without the bad. For example, the higher good of forgiveness requires the bad of wrongdoing. These arguments can account for some of the bad in the world, but I do not believe they can justify all the evil and suffering that exists.

Solutions to the Problem of Evil Are Not Possible Without Theistic Finitism

Classical theists would be quick to respond with further arguments and counterarguments, but this essay is already long enough and this subject deserves its own treatment. To summarize my view, as I have studied the problem of evil as it is debated primarily between classical theists and atheists, I find the atheist critique more persuasive. The world we live in is incompatible with an all-loving and all-powerful God as described in classical theism.

For Latter-day Saints, the problem is still challenging and solutions may involve speculating on things we do not yet know. But with finitism, I believe it is at least possible to resolve. There is an important difference between believing something is possible without knowing how, and believing something is impossible.

A Caution Against Over-Applying the Limits on God’s Power

After reading this, some might be tempted to resolve any theological difficulty by arbitrarily limiting God’s power, especially when addressing the problem of evil. However, God’s omnipotence is a central theme in scripture, so I would recommend exercising caution and proposing limits only when warranted by Church doctrine or when, after careful thought, they are required to make reasonable sense of a scenario.

I would especially avoid proposing limits on God when it comes to the natural world. The scriptures are full of examples of divine intervention of immense power throughout history. In theory, one could propose limits here. For example, perhaps under eternal law, the fallen world only allows so much intervention by a perfect being. And so God must intervene sparingly. While I don’t personally subscribe to such views and see them as overly arbitrary speculation, Mormon finitism does logically allow them.

My view on God’s power over the natural world is that He is classically omnipotent, meaning there are no limits whatsoever other than logical contradiction. This means that God can prevent all instances of suffering, evil, and doubt in the world. As with classical theists, I would argue that God does not intervene, not because He cannot, but because there exists some greater good that the bad allows for. But unlike classical theists, we as Latter-day Saints can appeal not only to logical necessity but also to eternal law and metaphysical limits to explain why that greater good is impossible without the presence of the bad.

Of course, unless there is scripture or Church doctrine to support it, it is important to recognize that we ultimately do not know the answers to these problems and thus we are ultimately speculating. Even so, Mormon finitism remains a useful tool for showing that a solution is possible, which can often be sufficient to resolve doubts.

Is a God of Limited Power Worthy of Worship?

A common critique of theistic finitism is that such a deity would not be worthy of worship. Whether that holds true depends entirely on what those limits on His power entail. Within the specific framework of Mormon finitism I have outlined in this essay, it should be abundantly clear that this is not a valid critique.

God is the ultimate being, possessing supreme authority over all existence. He possesses all the power it is metaphysically possible to have. He is our Father, who infinitely loves us and works to bring about our eternal joy and success. Obviously, such a being is worthy of worship.

Why Have I Not Heard of This?

While you may be aware of doctrines on the limits of God’s power, such as the rejection of creation ex nihilo, you may not have heard them synthesized into the idea that the scriptures teach a limited view of omnipotence, where God can do all that is possible but not all that is logically conceivable. You may also not be aware of how profoundly this departs from the rest of Christianity and the modern monotheistic world more broadly, or how significant the philosophical benefits of such a view can be.

The idea has been discussed in philosophical circles, but Mormon philosophy is not mainstream. Some Church leaders have addressed it, such as B. H. Roberts, who wrote:

The attribute “Omnipotence” must needs be thought upon also as somewhat limited. Even God, notwithstanding the ascription to him of all-powerfulness in such scripture phrases as “With God all things are possible,” “Nothing shall be impossible with God”—notwithstanding all this, I say, not even God may have two mountain ranges without a valley between. Not even God may place himself beyond the boundary of space: nor on the outside of duration. Nor is it conceivable to human thought that he can create space, or annihilate matter. These are things that limit even God’s Omnipotence. What then, is meant by the ascription of the attribute Omnipotence to God? Simply that all that may or can be done by power conditioned by other eternal existences—duration, space, matter, truth, justice—God can do. But even he may not act out of harmony with the other eternal existences which condition or limit even him.20

The Encyclopedia of Mormonism also discusses the topic. While it is not an official publication of the Church, the project was approved by the First Presidency and produced with the involvement of BYU, the Church Educational System, and contributors from multiple Church departments. Under its section on omnipotence it states:

The Church affirms the biblical view of divine omnipotence (often rendered as “almighty”), that God is supreme, having power over all things. No one or no force or happening can frustrate or prevent him from accomplishing his designs (D&C 3:1-3). His power is sufficient to fulfill all his purposes and promises, including his promise of eternal life for all who obey him.

However, the Church does not understand this term in the traditional sense of absoluteness, and, on the authority of modern revelation, rejects the classical doctrine of creation out of nothing. It affirms, rather, that there are actualities that are coeternal with the persons of the Godhead, including elements, intelligence, and law (D&C 93:29, 33, 35; 88:34-40). Omnipotence, therefore, cannot coherently be understood as absolutely unlimited power. That view is internally self-contradictory and, given the fact that evil and suffering are real, not reconcilable with God’s omnibenevolence or loving kindness (see Theodicy).21

On the section on Theodicy it reads:

Traditionally, the affirmation of God’s sovereign power is expressed philosophically by the concept of “omnipotence,” which means that God can do absolutely anything at all, or at least anything “logically possible.” This often accompanies the dogma that all that is was created ex nihilo (from nothing) by God. The conclusion follows that all forms of evil, even the “demonic dimension,” must be directly or indirectly God-made.

In Latter-day Saint sources, God is not the only self-existent reality. The creation accounts and other texts teach that God is not a fiat creator but an organizer and life-giver, that the “pure principles of element” can be neither created nor destroyed (D&C 93; TPJS, p. 351), and that the undergirdings of eternal law, with certain “bounds and conditions,” are coexistent with him (cf. D&C 88:34-45). “Omnipotence,” then, means God has all the power it is possible to have in a universe—actually a pluriverse—of these givens. He did not create evil.22

But why is this framing not more widely discussed or taught in the Church? Perhaps it is out of concern that describing God’s omnipotence as limited or “finite” would give critics more grounds to dismiss Latter-day Saints as non-Christian. Or perhaps it simply reflects a lack of engagement in the traditions of Western philosophy within the Church. Whatever the reason, I hope this essay has made it clear that Mormon finitism is not a heretical position, but the natural conclusion of revealed doctrines of the Restoration.

Conclusion

I believe Mormon finitism is one of the greatest doctrines providing intellectual support for the Restored Gospel. I do not think the Creation, the Fall, and the Atonement can be made plausible without the concept of a God whose omnipotence is limited by metaphysical impossibility. Nor can the scale of suffering and evil in the world be made sense of without it.

When Joseph Smith taught that creation ex nihilo is impossible, that intelligences are eternal, and that eternal laws exist, I don’t think he understood the extent to which he was laying down a theological framework capable of addressing some of the most difficult philosophical challenges that have confronted Christianity and classical theism for centuries. Among the doctrines that make Latter-day Saints unique, this is surely one of the most philosophically significant.

C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain.

Joseph Smith, King Follett Discourse.

Recorded in William P. McIntire’s notes of the Nauvoo Lyceum (5 Jan 1841), in the Joseph Smith Papers. Standardized wording as quoted in LDS Living.

Wes Morriston, “Creation ex Nihilo and the Big Bang.”

Hans Halvorson and Helge Kragh, “Cosmology and Theology,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Alice Y. Chen, Phil Halper, and Niayesh Afshordi, “Copenhagen Survey on Black Holes and Fundamental Physics” (2025).

The Kalām Cosmological Argument is a famous example arguing that the universe must have began to exist by act of creation ex nihilo by God. See an overview at Reasonable Faith by William Lane Craig.

“It is an open question for many whether time had a beginning or whether the past is infinite” (Gregory E. Ganssle, “God and Time”, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Also see Alex Malpass and Wes Morriston, “Endless and Infinite”, Philosophical Studies (2020). In physics, scientists have proposed models that allow for an eternal past, including theories of eternal inflation and cyclic or bouncing cosmologies.

See “The Idea of a Finite God,” Encyclopaedia Britannica. One recent example of a philosopher embracing finitism in response to the problem of evil is Philip Goff who wrote his reasoning in “A God of Limited Power.”

William Lane Craig and Paul Copan, Creation Out of Nothing: A Biblical, Philosophical, and Scientific Exploration (2004).

From a discourse given by Joseph Smith in 1839 as reported by an unknown scribe, Joseph Smith Papers.

Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual (2017), Section 93, quoting Joseph Fielding Smith: “Some of our writers have endeavored to explain what an intelligence is, but to do so is futile, for we have never been given an insight into this matter beyond what the Lord has fragmentarily revealed.” churchofjesuschrist.org.

Guide to the Scriptures, “Intelligence, Intelligences”: “the spirit element that existed before we were begotten as spirit children.”

Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual (2017), Section 93, quoting Joseph Fielding Smith: “There is something called intelligence which always existed. It is the real eternal part of man, which was not created or made. This intelligence combined with the spirit constitutes a spiritual identity or individual.” churchofjesuschrist.org.

See Blake T. Ostler, “The Idea of Pre-Existence in the Development of Mormon Thought.”

Paul Nolan Hyde, “Intelligences,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism. “the question of whether prespirit intelligence had individual identity and consciousness remains unanswered.”

Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, Part First, Section 6.

Hans Küng, On Being a Christian (1976).

B. H. Roberts, The Seventy’s Course in Theology, Fourth Year (1911).

David L. Paulsen, “Omnipotent God; Omnipresence of God; Omniscience of God,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism.

This is terrific, thank you! Two thoughts/questions:

1) For cases that talk about God not creating something already-perfect, I agree with what you said but to me it is just easier to think of it not so much as something He can't do, but simply that there is value in doing it that way; it's just a really effective solution to the problem at hand. As in, the experiences of mortality produce the desired result (I recall a GenCon talk from years ago that talked about how wind encouraged trees to form deep roots). Plus, our theology incorporates a critical additional idea: we chose this. This life isn't because of some cruel Being that likes to watch people suffer but something akin to "My child, here is a way that you can advance very quickly in a very short amount of time. There will be some really great parts, but there will also be a lot of pain and suffering. It will be difficult, but it will be a very effective way to teach you a lot of things and give you a ton of experience. Do you want to do this?" We said yes! We might not fully appreciate why first-hand experience matters, but it seems that it does.

2) Do you think that intelligence could be the term to describe the "stuff" out of which spirits are made, sort of as a parallel to what we know as the fundamental particles of matter? i.e. there are some fundamental physical particles that are organized into physical things and then intelligence would be similar in the sense that it is this stuff that just exists and can be organized to create greater, spirit-ish things. *An* intelligence could then refer to a spirit or a proto-spirit of some sort, i.e. it's a blob of intelligence that God organized into an individual child of His, an entity with an identity of its own and made up of enough intelligence to have the potential to advance forward to become more like its Father, but there could also be lesser spirits made out of less intelligence or organized in a lesser way, all the way down to things being composed of or having some intelligence but maybe not crossing the threshold to be considered a spirit. (I'm not necessarily saying we go all the way to panpsychism or Skousen's Intelligence Theory, but maybe something along those lines?)

Thanks for clarifying this. Your finitism argument is brilliant! It really resonates how even a divine system could have inherent, logical limits, kinda like a well-defined API.